Thursday (12th March 2020) afternoon’s post COBRA press conference with the Prime Minister Johnson provided an interesting update on the UK’s strategy to delay the spread of the Covid-19 coronavirus. It was interesting because it diverts significantly with what many other countries are doing to limit coronavirus spread, but in my opinion is also a very high risk strategy.

Competing Strategies

The strategy seems to be largely based on getting people to remain at home if they think there is even a relatively small chance that they have contracted the virus (UK Gov Stay at Home Guidance). Thus, if you believe you might be showing symptoms of illness, isolate yourself for the period of 7 days. To facilitate this we are to ask our “employer, friends and family to help you get the things you need to stay at home”, sleep alone when at home, wash our hands and stay away from vulnerable people. Only if symptoms persist beyond 7 days or worsen are we to seek the advice of NHS 111.

Essentially this is a request from the Government that we act to remove ourselves from the circulating population at the first sign of illness. Doing this will ‘flatten the curve’, reducing the peak number of cases at any one time, and also push that peak into the summer months. At which point the NHS will be better able to cope. Sounds great if it works, but will it?

This strategy is in rather stark contrast to a number of other countries that have imposed highly disruptive restrictions to people’s movement and behaviour. Such as Norway (and Ireland) that advises against gatherings and human contact (NIPH), and has essentially closed itself off (Visit Norway). Italy, currently the worst affected country in Europe, has also imposed tight restrictions even on things like movement and shopping (BBC News).

Its Complex

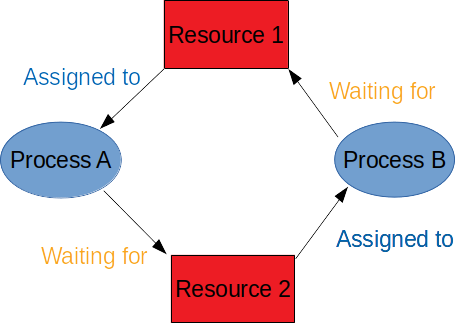

As a complex systems theorist this difference in intervention strategies is interesting. Complexity theory takes a view of the world as a system of interacting parts. It is also a relational worldview, which means it is not only the parts (such as people, buildings, objects general) that are important. The relationships between the parts, how they interact, is also important to how a system behaves. It is a systemic view.

The UK strategy seems to have at its centre the idea that a relatively small intervention in our behaviour, our relationship with each other and the world around us, will produce a significant effect on the spread of the virus. Self isolating at the first sign of illness, hand washing and so on. These changes are intended to flatten the curve of infection, lowering its peak, and move it to summer. This small intervention might be followed later by something more like what we have seen in Norway and Italy. The problem is, will such a small intervention limit the spread of pandemic flu?

Three Assumptions

There are at least three significant assumptions underpinning this strategy. On which its success depends.

One, people are willing and able to do it. They are assuming that people will do what they ask, and can do what they ask. There could be many reasons why people do not follow the advice. They might think that their symptoms have nothing to do with Covid-19, or don’t immediately recognise them as illness. Financially taking time off work might be impossible. Not all households have enough space at home to self isolate, including ‘sleeping alone’. Lack of compliance with the changes to behaviour will mean the virus spreads more quickly and they fail in their attempt to flatten the curve and shift the peak to the summer.

Two, they will know when to switch strategy. Central to the UK strategy is an ability to know if or when there is a need to switch from this modest intervention to a more draconian one. As at some point it is likely that more restrictions will be needed. When you do that is a trade off between wanting to shift that peak to the summer, and also limiting the spread. Also in the press conference was a decision to stop testing outside of hospital. By doing this they lose good data of how the virus is spreading in the population, making it harder to know when to change strategy. Perhaps making it harder to know when the system is approaching a tipping point into uncontrolled spreading.

There are hints that some of that data and analysis might be sought from big tech companes, with Buzzfeed reporting that Dominic Cummings will chair a “Tech CEO Round Table”. With the suggestion being that they have data that could help understand and combat the flow of coronavirus. This again is risky, as a source of data to understand viral spread social media is unproven, and perhaps this isn’t the time to be testing unproven methodologies. It does seem to betray some of the thinking within No. 10. That all problems can be manipluated through data and analytics, mediated via social media companies.

Three, changing behaviours will have the effect they predict. This assumption is more difficult to analyse and impacts any strategy. When we make changes to a complex system, in this case our day to day modes of interacting, working, and living. We cannot be sure that the system will react as we predict. It could quite easily do something unexpected, and that unexpected behaviour will interact with how the virus spreads. What that will do is currently anyone’s guess, but will soon be our lived experience. However it is an area of scientific study that we should focus more attention on. What are the systemic impacts of large scale interventions in societies? The types of interventions that will be needed to fight things like pandemics and climate change.

Is It a Good Strategy?

The logic of the strategy of countries like Norway is more simple that of the UK. There the idea is to be very restrictive and try to slow it down straight away. One would assume that they have factored in that it will not be fully complied with, some non-compliance with the restrictions will cause spreading of the virus. They might even be counting on that to spread it slowly to allow people to become immune without their systems being overwhelmed. This a shock to the system that they hope will flatten the curve.

The UK on the other hand is betting on compliance with their strategy, they need people to comply for it to spread slowly, flatten the curve, and move the peak. They are also assuming that they can spot the time when they need to move to Norway strategy should they need to. Both of these are more risky, in the sense that you are reliant on getting more things right. If people don’t comply the virus will spread rapidly through the population, and if they miss the time to change strategy then again it could get out of control.

Of course, if it works it will turn out to have been the right thing to do! However it is definitely very high risk, and the costs if it fails will be significant.